Joined up investments reduce health risks and burdens to people, livestock and ecosystems

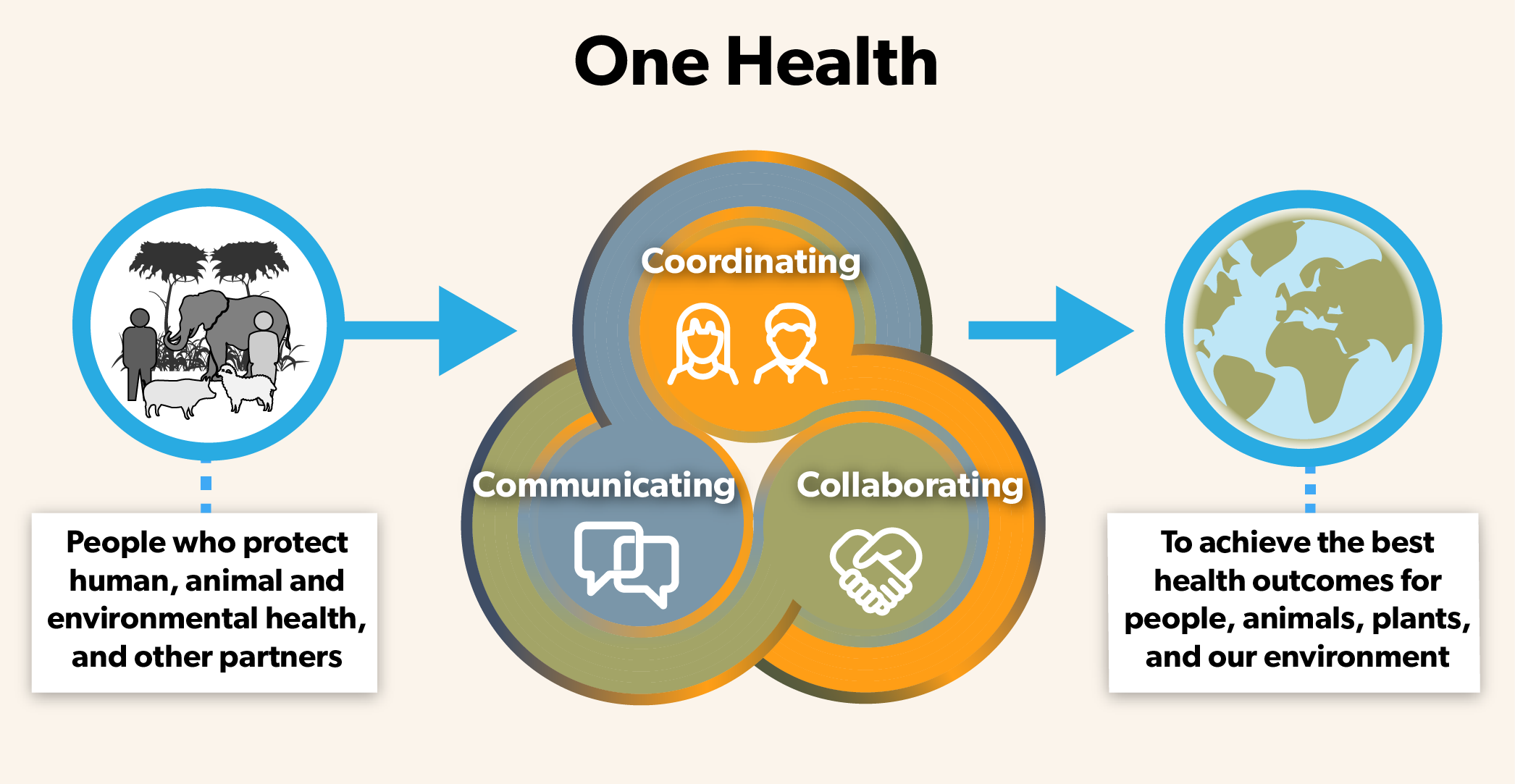

Complex health problems affecting people, animals and the environment are best tackled through integrated ‘one health’ investments and policies that unite and apply multi-sectoral medical, veterinary and ecosystem expertise.

Core message

Facts

- About 60 per cent of human infections are estimated to have an animal origin, and of all new and emerging human infectious diseases, some 75 per cent 'jump species' from (non-human) animals to people

- The biggest drivers of rising animal to human disease include: rise in demand for animal protein, unsustainable intensification of agriculture, land use change, urbanization, climate change, population growth.

- Thirteen diseases transmitted from animals to people are estimated cause 2.4 billion cases of human illness and 2.2 million human deaths a year.

- Foodborne diseases, many of which have an animal origin, cost poorer countries US$110bn a year in lost productivity and medical expenses.

- An estimated 700,000 people die every year from antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections as a result of AMR, nine out of 10 of these in poorer countries.

- Strengthening human and animal health capacity by the One Health approach could result in 10%–30% cost saving in surveillance and communication costs

One Health practices unite medical, veterinary, environmental and other expertise for healthy people, animals and lands.

A One Health approach requires a change in outlook and action. It demands a shift from a disease-focused approach to more systems-based one, rethinking the idea of innovation to embrace new ways of working as well as technological solutions, and sharing learning and evidence.

It means working alongside people from different backgrounds, specialisms and sectors, and being prepared to do things differently.

It shifts the focus from disease treatment and control to disease prevention, surveillance and preparedness.

One Health brings the added value to the society by having more knowledge, life saving for health or animal, and economical benefits.

A One Health approach brings all-round benefits. One dollar invested in One Health approaches can generate five dollars’ worth of benefits.

For example, the cost of treating and controlling bird flu (avian influenza) in people is vastly outweighed by the cost of vaccinating poultry against the disease. Savings can be used to build resilience to absorb health shocks.

One Health avoids duplication of work and services by having different stakeholders working towards a common goal, each contributing with their area of expertise, fostering synergies, avoiding duplication When disease outbreaks do occur, One Health minimises the lives affected and lost.

The siloed approach

Human health challenges in the past have been tackled by human health experts only, whether in government, in the private and non-governmental sectors or in the research world. In general, a disease-specific approach has been taken to disease management.

Likewise, animal health and environmental health challenges have been taken up by narrow specialists, independent of other health sectors.

Working together

But zoonoses and AMR must be understood in their wider contexts. That way, alternative, more effective and more cost-efficient routes to health that benefit ALL sectors can be put into action.

Rift Valley fever (RVF) disease in animals shows earlier than in people and can serve as an indicator for human health specialists to take action by taking preparedness measures such as sensitising high-risk groups such as meat handlers. This requires good cross sectoral communication. In 1996-7, an outbreak of RVC caught authorities in Kenya off guard. In all, 27,500 people became infected and 170 died. A more widespread RVF outbreak 10 years later resulted in just 700 suspected human cases and 90 deaths. The widely different outcomes have been attributed to a more coordinated response put into action in the later outbreak thanks to Kenya having adopted a One Health approach.

After the Avian Influenza outbreak in 2003, Viet Nam was one of the first countries in Asia to adopt a multi-sectoral approach. One health is integrated into all Government plans related to infectious disease and pandemic preparedness. It helped to contain and control several diseases such as SARS, HPAI and rabies. Vietnam developed and nationalised the Vietnam One Health Partnership at governmental level that serves as platform to bring institutions and actors in human health, animal health and the environment to work together to fight zoonoses, AMR and food safety. An academic One Health curriculum was developed by the Viet Nam One Health University Network to build One Health capacities for students (future leaders), lecturers, as well as human and animal health professionals at ministries and grassroots level. They work across sectors and disciplines and apply One Health in solving the problems on the ground.

In Ethiopia, approaches to participatory rangeland management are establishing One Health units to improve the health of humans, livestock and the natural environment. Better integration allows for better control of zoonotic diseases, helps to better tackle transboundary animal diseases through control programs and keeps an eye on the health of the rangelands themselves.

Around the world, animals and their products are involved in or impacted by many crimes. Such criminal acts, deliberate or accidental, harm or disrupt human, environmental or animal

health and welfare, food safety and authenticity, economic and social activity or national security. Recognizing the need for coordinated actions against animal agro-crimes, law enforcement agencies, customs services, veterinary services and public health agencies are working together in a one health approach to, for example, reduce the trade in wildlife products, enhance animal welfare, fight pet theft, stop the spread of harmful pathogens and control animal smuggling.

Globally, the World Health Organization collaborates closely with the Food and Agriculture Organization and the World Organisation for Animal Health to address risks from zoonoses and other public health threats existing and emerging at the human-animal-ecosystems interface. In 2020, the United Nations Environment Programme joined this ‘Tripartite plus’ collaboration signalling the importance and inter-connectedness of One Health interventions.

What can be done

- Mainstream One Health at policy and regulatory levels

It is essential that cross sectoral approaches are mandated and funded at all levels of government (national, state, district). This allows for joint planning and communication across departments and ministries. This can include establishing one health task forces or centres, establishing multi-sectoral surveillance and early warning mechanisms, setting up rapid response operating procedures and capacities, requiring one health assessments in policies and investments or raising political and public awareness.

- Build shared, collaborative One Health capabilities at technical and professional levels

One Health approaches should be incorporated into training and education in animal, human and environment health so health is understood in a holistic sense. It is important to establish inter-sectoral opportunities and incentives to share information, agree shared priorities, confirm roles and responsibilities and foster collaboration and resource sharing.

Where similar structures in terms of logistics, personnel and materials are required by multiple programmes, resources can be shared to increase efficiency and effectiveness.